Eastward the Course of Mission Meets the Market

On Slack, developers, and Silicon Valley Narratives

I have memories of the Slack IPO. Before I proceed, let me acknowledge that statement is kind of ridiculous for anyone to make, with the exception of maybe Stewart Butterfield or the investment bankers who looked on powerlessly as Slack opted for a direct listing instead of a Goldman and/or JP Morgan underwriting. So let me justify the statement with some context: at the time (2019) I was working as a stock investment analyst, a year into my first job out of college, and happened to graduate into a wave of IPOs that had been incubating for years in Silicon Valley while I completed my undergrad degree in history – Docusign, Dropbox, Zoom, Uber, Lyft, Slack (and others).

The reason the Slack IPO made such an impression on me – why it ranks in my early-20’s RAM alongside highlights like “doing molly at Elsewhere” and “dates with forward-deployed Palantir engineers” – is because it was the first time I began to realize the power of San Francisco as a cultural export machine. More specifically, it was the first time I considered that narratives can be distributed not just in the form of “the algorithm”, but through business imperatives. Are you born into the religion (algorithmic social feeds), or does a local prophet (your boss or head of procurement) seek counsel from an oracle (VP of sales) and deliver the Solution (Slack) to your lost community of white collar employees with their own bespoke remedies for problems that are instantly resolved 100% faster with the glowing out-of-the-box solution? I began to understand that software was a cultural export: a vision for how firms should run, seen through the lens of Silicon Valley.1

It was also the first time I really considered tensions between the visions of Silicon Valley and Wall Street (and by extension America, and by extension, the rest of the world). These tensions of course have metastasized into much larger issues with much bigger implications than those represented by chat software for coordination. But you have to start somewhere.The IPO was a proposition about who workers were. Sure, Slack was positioning itself as a replacement to email (something Wall Street and everyone else uses, obviously), but it was also a harbinger of a coming organizational shift, where developers and engineers would wield increasing influence in the office.

Slack's focus on developers at the time deserves attention. At their investor day presentation, management emphasized not just the number of DAUs (10 million) but the fact that developers constituted a significant portion of that population (more than 500,000, who had created 450,000 custom plug-ins for Slack in total). The subtext was that there was a secret but growing cabal of developer-first organizations (88,000, if we count by paid customers), and these companies were extending tech’s influence by cross-pollinating other tech platforms (like Atlassian, GitHub, PagerDuty, and Zapier) directly into chat. Slack was where developers would chat and the products they built would interoperate. It was kind of a microcosm for San Francisco.

If a decision to invest in an IPO could be framed as a question around belief, the question of whether or not to invest in Slack might have been whether you thought developers would comprise an ever-increasing portion of the workforce, and if they could make Slack itself more useful by leveraging their integration-seeking prowess to turn the product into a platform. Even if you, as a firm, might not personally experience all the benefits of Slack, you could squint and see how a growing number of engineering grads, an infusion of VC money into SaaS companies, “digital innovation” efforts undertaken by Fortune 500’s, and shifting preferences toward casual communication and away from the staid formality of email could create the right environment for Slack to be extremely successful. Slack’s vision was a pretty good one, except there was just one problem.

The same year that Slack IPO’ed, Microsoft announced that their Teams product was on its way to 13 million DAUs (Teams launched two years prior in 2017). While Teams also supported third-party integrations, the focus of course was on a tighter integration with Microsoft’s core products like Outlook, Word, Powerpoint, and generally owning the touchpoints between an office-worker and their tools. The market eyed this warily: Slack was pretty much the only COVID-era SaaS stock that wasn’t buoyed by the work-from-home thesis. By December 2020, Teams had 145 million users. That same month, Slack was acquired by Salesforce for $27.7 billion, when it had 12.6 million users. Stock ticker poetry: WORK acquired by CRM.

And so, another popular Valley narrative got airtime: the one where Microsoft uses their headstart on hardware and business license distribution to ruin things for everyone. In the mid to late 90’s, Microsoft kneecapped the proliferation of Netscape and other browsers because it tied the distribution of its Windows operating system to Internet Explorer. In the late 90’s, Microsoft pissed off Eric Raymond (of “The Cathedral and the Bazaar” renown) and pretty much every developer in the open source community when their strategies to spread FUD and undercut the adoption of Linux became well-known. In 2020, Slack filed an antitrust complaint against Microsoft. More recently, reports emerged that OpenAI is considering suing Microsoft for anticompetitive behavior, ostensibly related to the (now scuttled) Windsurf acquisition, but likely more motivated by OpenAI’s desire to onboard more cloud hosts for its API, like Google.23

There are two ironic things about the way the Slack saga played out:

Microsoft arguably was the original creator of the developers” meme. Credit where it’s due.

Slack was probably right about the influence of developers. Just not in the way they thought (more on this later).

In the Hands of the Unintended

A good indication of a technology’s rate of proliferation is how fast it ends up in the hands of people it was not intended for. Reddit was (allegedly) for incels and memestock traders, but it’s now $40bn market cap company that everyone uses or at least visits. In their S1, Figma touted that 2/3 of their customers are non-designers. Push notifications were originally a tool invented by BlackBerry developers to save people time while checking their phone; now they’re used by viral growth hackers to command your attention. China manufactures drones that end up in the hands of Russia and Ukrainian fighters. Before Slack itself was a chat product for teams (and then, a growing number of developers) it was internal chat for a game the original Slack team had built pre-pivot.

A similar rule of thumb can be applied to narratives: the stories that captivate us the most are ones where the things that were never “supposed” to happen do. Brexit and the 2016 election. The collapse of SVB. Apple leaning on OpenAI to power AI-enabled Siri. The release of DeepSeek, and China generally overtaking the US on tech.

I’d argue that Silicon Valley’s most successful export is the narrative that we need more developers. Or at least needed them. You can trace a narrative throughline between “Software is Eating the World,” to the Obama-era “Learn to Code” initiatives which saw reinforcement from the likes of Bill Gates, Mark Zuckerberg, Jack Dorsey, et al, to a 2018-era report from Stripe arguing that developers could contribute $3 trillion to the world’s GDP over a period of 10 years4, to a 2019-era Biden telling coal miners (?!) to learn to code. It was the economic mobility panacea of the 2010’s. And this was arguably the narrative that led to Slack deciding to focus on “developers” as a key user cohort when they went public in 2019.

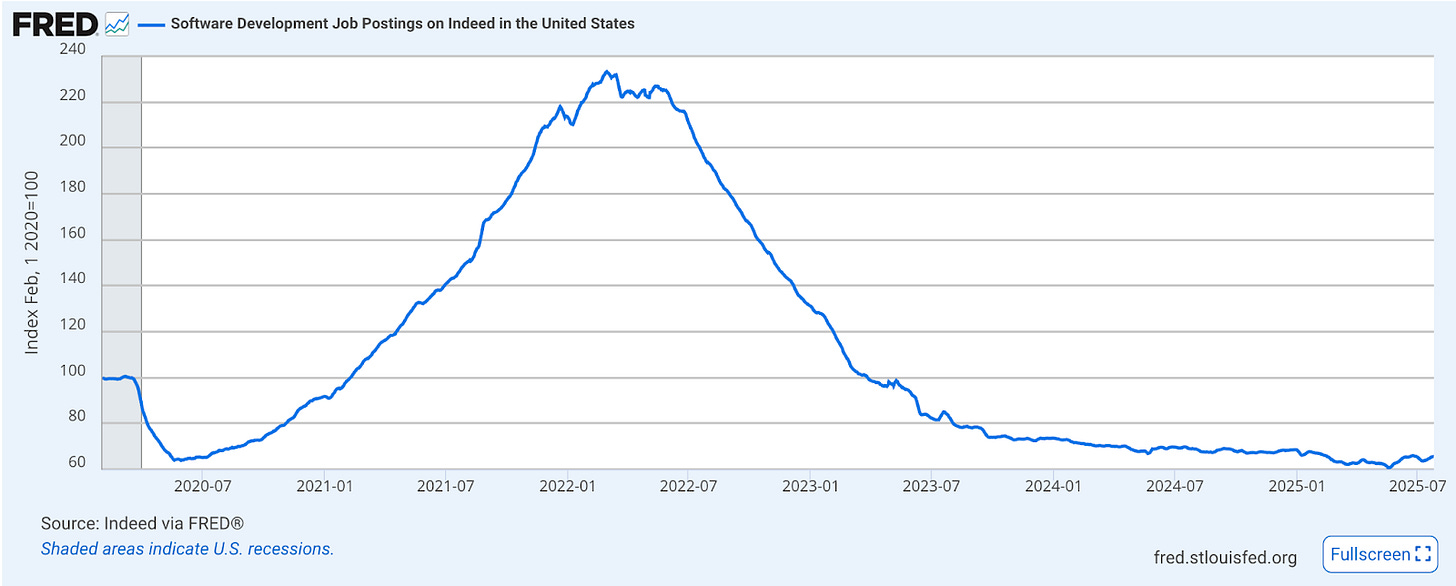

Then, in 2022/2023, cracks started to appear. The ZIRP era ended. AI models got better, leading some to believe a hollowing-out of the middle layer of developer talent was either imminent or already underway. This chart, highlighting a slowdown in developer hiring, made the rounds a few weeks ago.

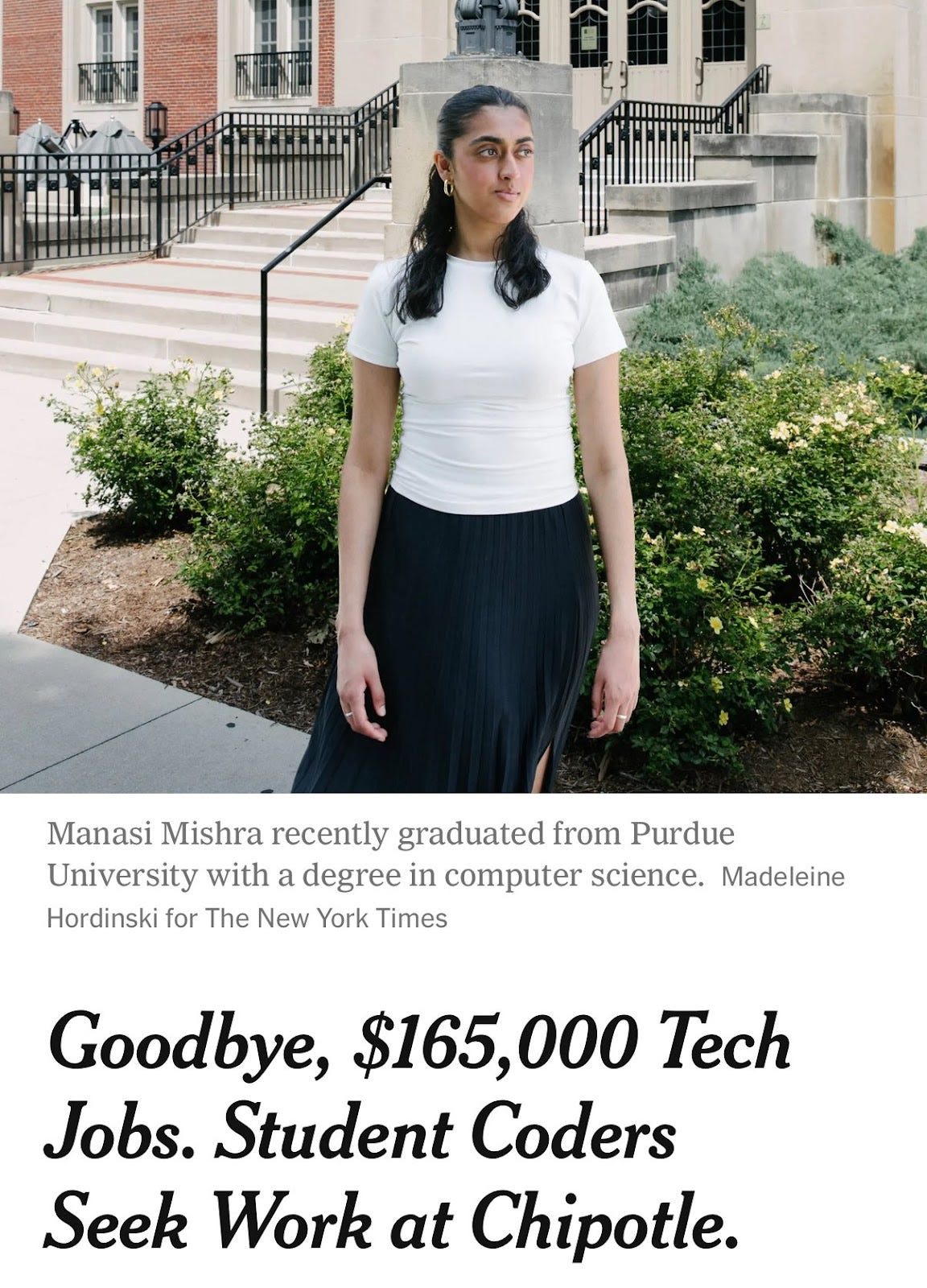

And this story made the rounds on X over the weekend.

People are choosing to interpret this in different ways. In the “hysteria” camp, we have the folks who argue that students have been lied to, that opportunities are drying up, that AI is taking everyone’s jobs, and that time is limited to “escape the permanent underclass” (and that the equally dark Janus head of “permanent underclass” is “getting oneshotted.”). In the sanguine camp, we have the argument that new job postings are generally declining, and that the decline in jobs at traditional firms might actually be a good thing: it gives younger generations the opportunity to be scrappy, build opportunities for themselves, and perhaps even escape the one thing worse than the permanent underclass: a lifetime of being stifled.

When the “clear” narrative of the past era deteriorates, you get competition for the new dominant narrative. So between the above two, which one is right?

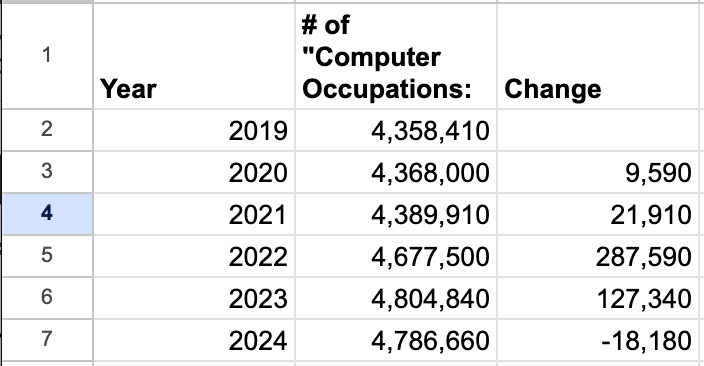

Using the Occupational Employment and Wage Statistics data from the BLS (insert obligatory “can we even trust that data?” caveat here) I charted out a quick look at the number of Americans employed in “Computer Occupations” in the United States from the same period as the FRED chart above. The data for 2025 isn’t available yet, but trends do seem to confirm the former camp: in 2024, the number of developers employed in “Computer Occupations” declined in 2024.

So what about the sanguine camp, and the narrative that scrappy devs are building apps with small teams of other developers or commanding a small army of agents to do their bidding? Is there any concrete data that tells us about the strength of these narratives, or do we only have Paul Graham posts about founders writing 10,000 lines of code to point to?

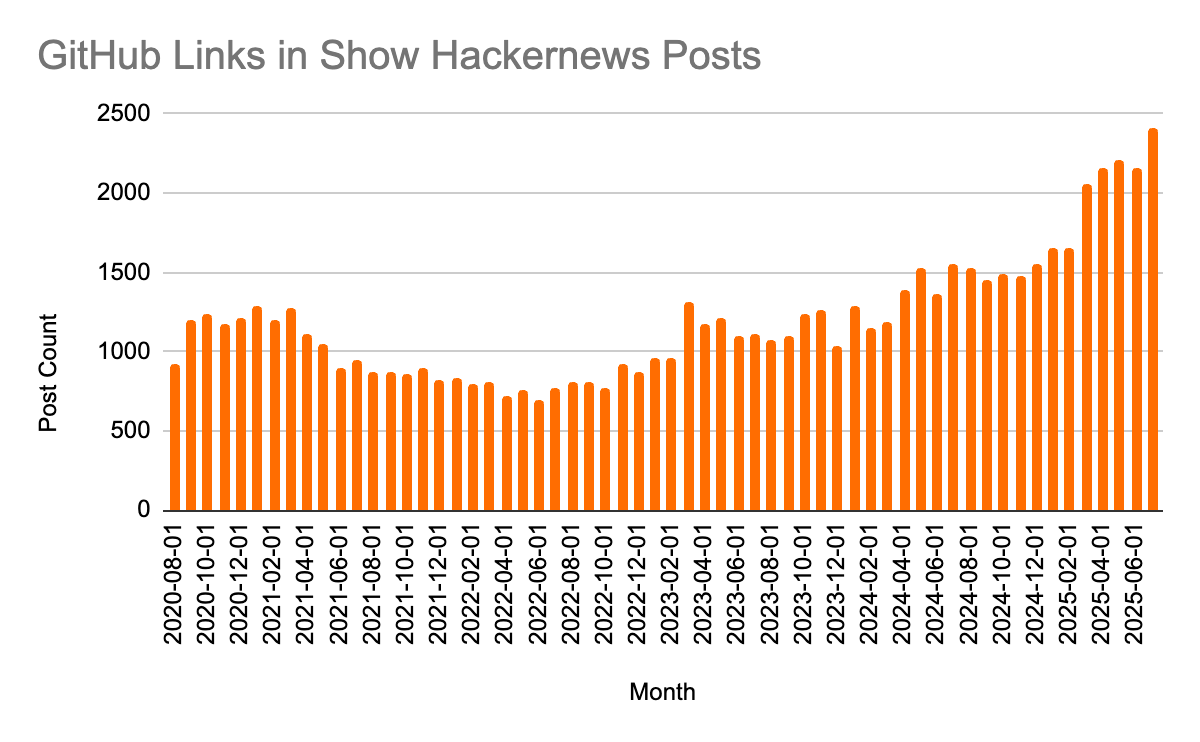

We may not have government-sanctioned data, but there are still ways to try to directionally assess this. In fact, we can keep things in the YC family, and look at aggregate post data from Hacker News, the Reddit-esque forum focused on startup founders. In 2021, Hacker News made their dataset available on Google’s BigQuery to anyone looking to run analysis on it. With the help of Chat-GPT, I ran a query to determine the number of posts on “Show Hacker News” that link out to GitHub, as an attempt at proxying the number of “solo” or “small team” developers who are actively working in public. If you regularly look at Show Hacker News, you’ll know that the activity in aggregate is mostly developers looking for feedback and early distribution on their passion projects, rather than people sharing repositories of large, foundation/corporate-sponsored open source software. So it might be a decent indicator of whether the number of solo developers is increasing.

Funnily, this chart almost looks like the inverse of the FRED “Software Development Job Postings” data above: a trough in 2021-2022, and a steady rise starting in 2023 (right when Chat-GPT was released).

While this data just captures the level of social excitement around public GitHub repositories (so it doesn’t capture small teams of developers who might be building closed-source consumer applications or any other kind of software product), here are a couple of ways that one might interpret the data:

As the amount of new jobs in software leveled off, developers decided to get creative, and started building projects that could one day turn into companies. While Chat-GPT and other LLMs made it possible to do this faster, and at a higher degree of volume than before, the idea that you can turn a repo into a company has been around for awhile. As an example, Segment, a customer data platform, started as an open source repository which launched on Show Hacker News in 2012 (it later sold to Twilio for $3.2bn). Maybe there are a larger number of people attempting this now, and these people are okay with smaller outcomes (this might be best captured by the “indie hacker” movement, or the idea that you can have a good-quality lifestyle building software products that allow you to live on $100-200 ARR annually). I’m arguing that open source software here is a proxy for these wider trends (not all open source projects monetize, but some do have a freemium business model).

LLMs also have second-order effects. There’s a growing demand for open-source frontends that allow developers to coordinate and tweak how they interact with models: if you look at HackerNews every day, you’ll see that many of the projects are frontends for orchestrating how developers interact with LLMs. Emboldened by AI, developers are creating more software and releasing it publicly (even if the underlying models that enable these projects are closed source). Some of it is long-tail software, for an audience of one. But some of it will lead to new companies built around open source projects that reach enormous scale. As just one example: Ollama, a platform for running LLMs locally, ranked among the top ten open source projects on GitHub by commit count.

Maybe this is unsurprising: “developer” is just as much a job title as it is a skillset. Even if jobs that are captured by FRED or BLS-level data go away, the number of developers in the world actually only ever increases (as new developers graduate from universities). These developers want to do something: keep their skills sharp, prove their value. More software gets built publicly as a result.

Let’s say that the developer meme was a “bubble” that reached its peak sometime around 2022-2023. Even if developers aren’t seeing the same level of demand at companies anymore, they’re still developers. So the “bubble” is very different from financial bubbles: the core asset of the developer hasn’t gone anywhere. What does this mean? People are going to find new ways to build, share, and monetize their work.

Again, the Show Hacker News data is just my attempt at designing a proxy for the larger trend of solo developers building projects. I know it’s not perfect or definitive. But it does point at a kind of directional “truth” that gives some legitimacy to the sanguine narrative camp: the developers are building. Whether or not they’re part of large companies (the kind that uses Slack, Teams, or otherwise) is another question. But they’re definitely not going anywhere.

Coda

A few years ago, I visited my brother in San Francisco. While we were walking along the Embarcadero, he made an observation that, as he framed it, was a metaphor for the Silicon Valley condition: “Mission and Market Street don’t intersect.” Geography is destiny: Silicon Valley creates the narrative, and it’s up to the rest of the world to embrace, reject, and/or warp it as they see fit.

Somewhere, there is a parallel universe where Stewart Butterfield is conducting Slack’s second quarter earnings call. The amount of developers using Slack is one of “The Numbers” that Wall Street pays close attention to: it’s their indication of the platform’s stickiness, utility, and overall influence among its customers. Marquee customers are rolled off at the top of the call: “We’re proud to say that everything runs on Slack at OpenAI.” Cursor uses Slack. Linear uses Slack. And then Stewart gets his first question: “We’ve been seeing reports that the rate of developer hiring is slowing down – what does this mean for Slack’s users? Are you starting to see a softening on your end? Stewart takes a deep sigh and begins. The story isn’t quite what you think.

A more succinct way of writing this paragraph: I learned about the existence of B2B SaaS

Anyway, we need a new Law on the order of Moore’s and Metcalfe's. Microsoft's Law: every piece of litigation against Microsoft is a desperate cry to split the timeline, and use the courtroom as a counterfactual world to simulate how things could’ve been. Because the “Microsoft ruins everything” narrative isn’t really about Microsoft, it’s about the desire to let innovation and change naturally play out instead of being stymied by a corporate leviathan with its own interests.

(I personally have nothing against Microsoft to be clear)

The methodology in the report is kind of funny, and basically argues that developer inefficiency (especially in France, where developers, statistically are the least efficient) represents a $300 billion drag on yearly GDP - so if developers became more efficient, we’d see aggregate GDP increase

Interesting article. Small nerdy detail, the OEWS uses a three year panel. In other words, only a third of the 2024 data actually comes from 2024. That makes interpreting the time series a bit tricky. Something like the American Community Survey (ACS) might be better for this task (although that data has its own quirks).